Mussels of Berlin

I visited the Senckenberg Research Institute and Museum in Frankfurt to look at their collection of freshwater mussels, specifically those that had been found in Berlin and Brandenburg.

Introduction

I visited the Malacology (Mollusc) department at the Senckenberg two weeks ago to look at the items in their freshwater mussel collection from Berlin-Brandenburg.

The Senckenberg has an important collection of freshwater mussels (by which I mean the shells of freshwater mussels), that have been collected historically, with the vast majority being collected in the nineteenth and first half of the twentieth century. There is also an impressive collection of soft body specimens (ca. 450 lots), but from the vast majority of mussels only the shells (ca. 20,000 lots) were brought to the museum. It is, according to the website, one of the largest and most scientifically significant collections in the world, with specimens of all European species covering almost all European water systems. Its significance is also due to the high number of ‘type’ specimens it holds. Types in natural history collections refers to the examples upon which the species description was based (‘holotypes’) or substitute specimens that serve as the type specimen (‘lectotypes’). The website also features a ‘Naiad (freshwater mussel) of the Month’ documenting the ongoing process of cataloguing collection items (something that, as an ex-Librarian, I have a lot of familiarity with and sympathy for; an enjoyable but seemingly never-ending and invisible labour).

My first encounter with the Senckenberg Research Institute and Museum was at Euromal 10, the 10th European Congress of Malacological Societies, in Ιράκλειο (Heraklion), Κρήτη (Crete). Julia Sigwart, Head of the Malacology department, gave one of the keynote talks, with a presentation titled “What do whole genomes tell us about molluscan evolution?” This is a particularly interesting question because the mollusc phylum is enormously biodiverse, including a range of such anatomically varied invertebrates as octopuses, squid, nautiluses, cuttlefish, snails, slugs and clams.

Malacology is, non-evidently, the study of molluscs (mollusca / molluska). To which, just as non-evidently, my group of interest – the freshwater mussels (Süßwassermuscheln) – belong. The words malacology and mollusc both derive from the Greek: malakia, from Aristotle’s classification of soft bodied animals; and mollis, meaning soft. The same meaning is also found in the German term for mollusc, Weichtiere (Kodirov 2011). Surprisingly, these soft-bodied animals have the most diverse array of forms; as one of the Senckenberg researchers put it in a groundbreaking new paper: “Mollusca exhibits the widest disparity of body plans in metazoan evolution”, and observing that “the phylum further encompasses many … unfamiliar experiments in animal body-plan evolution” (Chen et al. 2025, p1001). Chen proposes that the flexible genome of molluscs has led to this fascinating flexibility of form.

My own interest, for my current project as a Fellow at RIFS (Research Institute for Sustainability) ‘The Rural Cosmopolis’, is in the adaptability and biodiversity of the freshwater mussel mollusc and what might be extrapolated from this flexibility for thinking about creative ecological processes and concepts for urban environments. Freshwater mussels’ presence is an indicator of healthy freshwater systems, but they are globally endangered. I therefore also wonder whether anything can be learned for risk management from the conservation of mussels.

Given the expertise in mollusc biodiversity and the large type collection at the Senckenberg, I contacted Julia to arrange a visit. She put me in touch with their resident mussel expert, Karl-Otto Nagel, who has an extensive knowledge of the species, having worked with them for decades and published prolifically, recently completing the Herculean task of compiling the Type catalogue of the Senckenberg freshwater mussel collections. Below is what I learned from the collection and – mostly – from Karl’s vast knowledge of freshwater mussels.

Image: Unio pictorum mussel shells in the Senckenberg collection.

Mussels of Berlin and Brandenburg

I discovered that there are six species of freshwater mussel in the Senckenburg collection historically found in Berlin-Brandenburg, which agrees with current literature on the topic (Landesamt für Umwelt 2018). These are: the Unio crassus, or Thick-shelled mussel; Unio pictorum, the Painter’s mussel; Unio tumidus, or Swollen river mussel; Anodonta cygnea, the Swan mussel; Anodonta anatina, Duck mussel; and Pseudanodonta complanata, the Depressed or Compressed river mussel.

The Duck Mussel (Anodonta anatina) is a common pond mussel that is highly adaptive. It can equally inhabit calm streams, rivers, lakes and creeks at depths of around 2-3 metres, in both muddy and sandy substrates. It adapts physiologically to differing conditions; in waters with poorer nutrient content it is smaller, while it can reach large sizes in fish ponds. Its adaptive capacity may also be observed from the high variation of its shell. It can tolerate stronger currents than its close relative the Swan Mussel (Anodonta cygnea), which prefers standing water, including still areas of rivers. The Swan Mussel is less varied in form, with a thinner shell. It inhabits substrates of fine, soft mud.

European Anodonta species tend to hermaphroditism (having both female and male sexual characteristics) in slower-moving waters (Lopes-Lima et al. 2016, p17), including the Swan Mussel. As Karl pointed out, the Swan mussel is a hermaphroditic species in which there are only hermaphrodites and females, and “males only” have not yet been encountered. In addition, hermaphroditic animals have been detected in all native European river mussel species (Yanovich et al. 2010). Their proportion in a population is usually not very high and whether there is a “strategy” behind this is only known for the freshwater pearl mussel (Margaritifera margaritifera).

Hermaphroditism maximises the chances of reproduction, which is harder for mussels in still water because the males (or male organs) release sperm into the water column, where it passively drifts with the current and may or may not be inhaled by a female (or hermaphroditic mussel).

The Painter’s Mussel, Unio pictorum, has varying shell shape and colour and an elongated fairly shallow oval form coated with white nacre – a pearly substance – on the inside of the shell. Its smooth, long and gently rounded shape and the whiteness of its interior made it an ideal palette for mixing artists’ paints, which is where it gets its name from. All freshwater mussels (order Unionida) have a shell composed of a thin outer organic layer, called the “periostracum”, and an inner (mostly) inorganic calcareous layer which in itself is made up of an outer prismatic layer and an inner (towards the soft body) nacreous layer. The Painter’s Mussel lives in sandy or silty substrates up to six metres deep of rivers, sometimes lakes, reservoirs and canals.

The Swollen River Mussel Unio tumidus is a wedge-shaped mussel that prefers weaker currents. It differs from the Painter’s Mussel in shape and thicker shell, with thickened teeth and a double-looped ‘umbo sculpture’ – the narrowest rounded part of the shell on either side of its hinge. It is a solid, fat oval, moderately inflated.

The Depressed River Mussel Pseudanodonta complanata is very rare in Germany. It has a flat, oval shell with little variation in shape, inhabiting the slow waters and muddy bottoms of old river arms and the edges of lakes up to 11 metres depth. It is extremely sensitive to water pollution and algal blooms, which may go some way to explaining its current rarity.

The protected Thick-shelled Mussel Unio crassus similarly inhabits clean rivers, preferring the middle sections, and smaller lowland running waters. It lives in stony and sandy substrates, usually completely immersed in it, but not in contaminated mud. The young are highly sensitive to pollution like the endangered Depressed River Mussel, and require high oxygen content. Adults don’t reproduce in running waters if the nitrogen content is too high.

Adaptations and Threats

“Throughout the long evolutionary history of Mollusca and continuing today, aspects of a flexible genome led to a flexible phenome: Endless forms of mollusks showcase the power of animal evolution.” (Chen, Z. et al. 2025, p1006)

“While studying the Naiad-shells of the upper Ohio-drainage, the fact was forced upon my mind, that certain species which inhabit the headwaters and smaller streams are represented, in the larger streams, by different, but very similar forms, which are distinguished from them chiefly by one character, namely obesity. The headwaters-forms are rather compressed or flat, the large-river- forms more convex and swollen. I also found that in the rivers of medium size intergrades between the extremes were actually present.” (Ortmann 1920, p269)

I learned a lot from Karl about mussel adaptations to their varied watery habitats (any errors below are certainly my own). He also introduced me to Ortmann’s Law of Stream Distribution. I had come across descriptions of mussel species by A. E. Ortmann previously, while doing a fellowship in John Pfeiffer’s Freshwater Mussel Biodiversity and Conservation Lab at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. Arnold Edward Ortmann was a malacologist who was actually born in Magdeburg, Germany, and did his PhD at Jena under the famous zoologist Ernst Haeckel. He emigrated to the United States in 1894, where he was the Curator of Invertebrate Paleontology, Princeton University until 1903, and then Curator of Invertebrate Zoology at Carnegie Museum, Pittsburgh.

Ortmann was a prolific describer of mussels and his work is still considered valid today. Ortmann’s law posits that the appearance of mussels varies depending on their habitat – in essence, mussels shell-form adaptations are environment-specific – with environment-related variations observed even within the same species. For example, rounder shells appear in stronger currents. I described some of these adaptations above in relation to the Berlin-Brandenburg species’, along with other physiological adaptations to environments.

What I initially take from this is the idea that we might adapt ourselves (and, by extension, our technologies) to work with our environments more than changing our environments to accommodate our desires. This seems to be a very simple thought, but it is one that actually demands a shift in perspective. To get a bit of (literary) distance on it, it is like the difference in science fiction between terraforming and the recently-coined term but old idea of somaforming.

In much outer-space-exploring science fiction, people arrive on a new planet and colonise it through terraforming, turning its native ecosystem into a habitat for humans. These both mirror what we are doing to our own planet (for example, the extractive processes depicted in Frank Herbert’s Dune), and respond to its environmental crises by imagining new, often ecological ways of terraforming other planets, which likewise stand in for our own planet. As Chris Pak points out in his book on the topic, terraforming in science fiction speculates on a range of environmental events and solutions (Pak 2016). Somaforming, on the other hand, means changing our physical bodies to be able to live in alien environments (which could, equally, represent our own planet). It is a light-touch, non-extractive approach; intergalactic eco-settlement if you like. The term seems to have been coined recently by SF writer Becky Chambers (2019), but variations on the concept recur throughout feminist science fiction in particular. In the case of Becky Chambers’ ‘To Be Taught, If Fortunate’ (2019), bodily modification to suit new planetary environments is achieved through enzymes. This recalls Donna Haraway’s Children of Compost stories (2016), a speculative fiction about a future where children are modified with genetic material and microorganisms of a chosen endangered species, giving them an empathy for and mission to protect that species. In earlier, feminist science fiction interspecies empathy and environmental connection are somatically generated through interspecies transplants and human-alien relations resulting in new species’ of children (for example, in Octavia Butler’s Xenogenesis trilogy (1987-1989) and Naomi Mitchison’s 1962 Memoirs of a Spacewoman).

The ecofeminist approach to water offered by hydrofeminism describes how so many of the terraforming projects of our time are related to controlling water (through river straightening, damming and irrigation, for example) (Neimanis 2019, p161). It shows the environmental effects and geopolitical inqualities this has created, in the wider context of anthropogenically aggravated water crises, from drought to flooding. Astrida Neimanis’ hydrofeminist work aims to “reimagine embodiment from the perspective of our bodies’ wet constitution, as inseparable from these pressing ecological questions” (Neimanis 2019, p1). What might hydrofeminism look like from the speculative perspective of freshwater mussels’ highly adaptive soft watery bodies and hard, aquaformed and terra(aqua)forming shells?

Freshwater mussels both terraform and somaform ecologically. They change their environments as well as changing themselves. They change their environments for the better, while their shells and physiological systems coevolve with their environments and the other species’ they share them with, especially the fish that carry juvenile mussels to new habitats (there is not space to delve further into this here, but it will be the focus of a future post. Meanwhile, I have previously written speculatively on the topic in several places (here and here). Freshwater mussels are like shapeshifting gardeners of the riverbed and water column, growing into and with their environments.

Risk

Of the six Berlin-Brandenburg mussel species, the Unio crassus is one of two species of mussel legally protected by European regulation, under the Flora, Fauna and Habitats Directive (1992). (The other being the more widely known freshwater pearl mussel, Margaritifera margaritifera, which has long been hunted for its pearls.)

There is a sense that there are other endangered freshwater mussel species that could also be included, but are not. Under the European Flora, Fauna and Habitats Directive (FFH), commonly referred to as the Habitats Directive, member states are bound to report on the status of protected species every six years, and are responsible for maintaining and – if needed – taking measures to conserve and rewild populations.

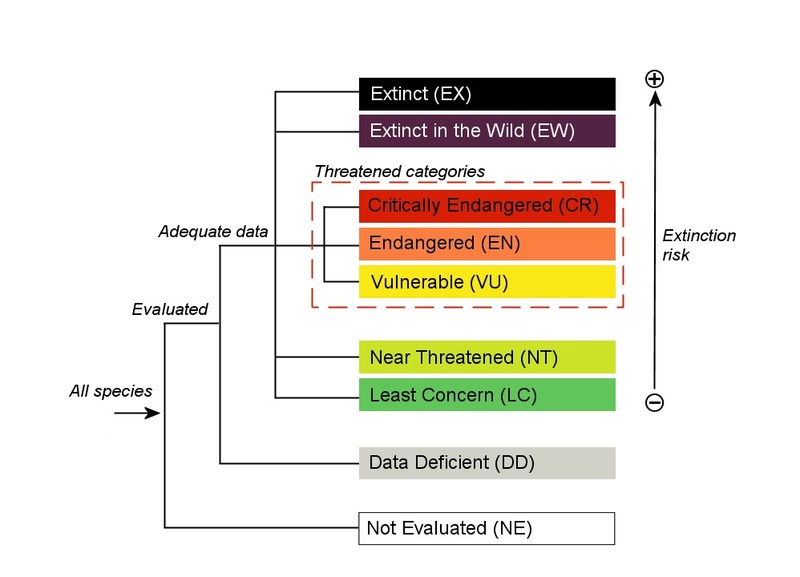

Unio crassus is classed as Endangered in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, and its population status is Decreasing. The Red List shows that, of the other Berlin-Brandenburg species, Pseudanodonta complanata is also Endangered and Decreasing. Anadonta anatina and Anodonta cygnea have decreasing populations but are classed as Least Concern, meaning they have a lower risk of extinction but are still important in terms of global biodiversity. Unio pictorum and Unio tumidus are also classed as Least Concern, but their population status is Unknown.

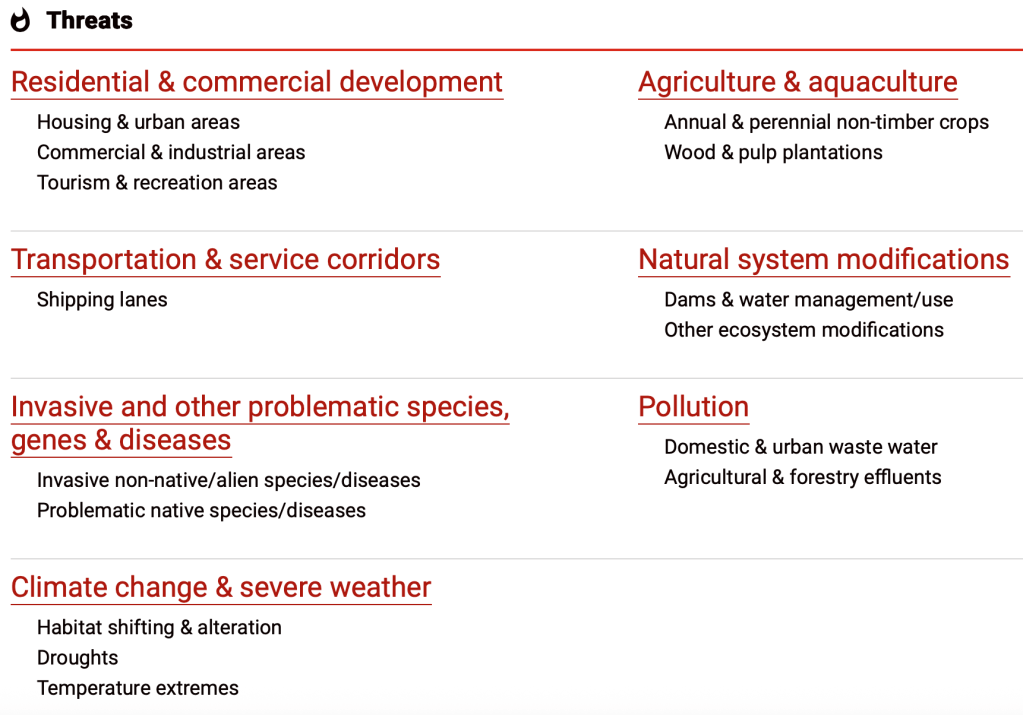

The IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Red List offers a regularly updated comprehensive assessment of animal, fungus and plant species extinction risks. It is an incredible tool for understanding global biodiversity, the status, geographic range of and threats to individual species. The threat classifications are especially illuminating. It lists the top-level threats and then gives further, specific detail about the nature of the threats to the species in question. For the Thick Shelled Mussel, it lists seven top-level threats, one of which is climate change and severe weather. The relevant sub-categories given are habitat shifting & alteration, droughts and temperature extremes. The more detailed view divides the risks into ecosystem stresses and species stresses, effects of these, timing, scope and severity. We see that in this case, for all sub-categories, the effects of ecosystem degradation, species mortality and species disturbance are ongoing, leading to slow, significant declines.

The Red List makes very clear what the risk factors are and their severity of impact, which in turn should make the task of deciding priorities for conservation and issues to address relatively straightforward.

Conservation

There is a current project in Brandenburg, Bachmuschel, to preserve and increase existing populations of the Thick Shelled River Mussel (Unio crassus) in 10 river systems in the Elbe, Havel and Spree catchment areas. This involves creating and upgrading habitats, as well as rewilding historically populated watercourses, or sections where the species are thought to be extinct, to establish new populations. It involves developing and promoting stocks of the host fish the species need for distributing their young; introducing hard substrates and dead wood, restoring the watercourses’ ecological continuity; relocating straightened watercourse sections back to their old courses, to restore former mussel habitats; planting riparian trees to regulate the temperature of watercourses through shading; installing sand traps to reduce the sediment load as a risk factor; closing drainage ditches to reduce nutrient loads from drained peatlands as a risk factor; installing hedges and constructing fences to reduce sediment input from agricultural land.

It seems that this kind of mussel-focused conservation project would also benefit human use of the river, prioritising cleaning and cooling. This will presumably have a positive impact on water supplies as temperatures increase, both through cleaner water (requiring less treatment) and less evaporation (so retaining more of it). It seems that it is possible to do this, while also allowing continued use of the much of the surrounding land with minor adaptations – although it is unclear how much impact unstraightening sections of water courses will have on land use (to be investigated further!).

Conclusions

While there is more to be explored about mussels’ adaptations, and especially those specific to the water bodies of Berlin and Brandenburg, the idea of low-impact bodily and land adaptations with an emphasis on changing ourselves first and coevolving with the environment second – and rather than imposing onto it – are key. This is not a new idea, but the change in perspective and priorities it requires represent an enormous shift.

If the Red List information about mussels was incorporated into freshwater policy and practice, might that ecologically transform waterways with beneficial effects for humans too?

The alignment with hydrofeminist approaches is a lens to be explored throughout the project and in further blog posts.

References

Butler, O. (1987-1989). Xenogenesis (Dawn, Adulthood Rites and Imago). Grand Central Publishing.

Chambers, B. (2019). To Be Taught, If Fortunate. Hodder & Stoughton.

Chen, Z. et al. (2025). A genome-based phylogeny for Mollusca is concordant with fossils and morphology. Science 387, no. 6737 (2025): 1001–1007.

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

Kodirov, S. A. (2011). The neuronal control of cardiac functions in Molluscs. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology, 160(2), 102-116.

Landesamt für Umwelt (2018). Naturschutz und Landschaftspflege in Brandenburg 27 (4).

Lopes-Lima et al. (2017). Conservation status of freshwater mussels in Europe: State of the art and future challenges. Biological reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. DOI: 10.1111/brv.12244.

Mitchison, N. (1962). Memoirs of a Spacewoman. Victor Gollancz Ltd.

Ortman, A. E. (1920). Correlation of Shape and Station in Fresh-Water Mussels (Naiades). Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society , 1920, Vol. 59, No. 4 (1920), pp. 268-312. https://www.jstor.org/stable/984426

Pak, C. (2016). Terraforming: Ecopolitical transformations and environmentalism in science fiction. Liverpool University Press.

Yanovych, L.N., Pampura, M.M., Vasilieva, L.A. & Mezhherin, S.V. (2010): Mass hermaphroditism of Unionidae (Mollusca, Bivalvia, Unionidae) in the Central Polissya region. – Reports of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine 2010(6): 158-163. [in Russian]

Leave a comment